|

It is divided into five sections: |

|

|

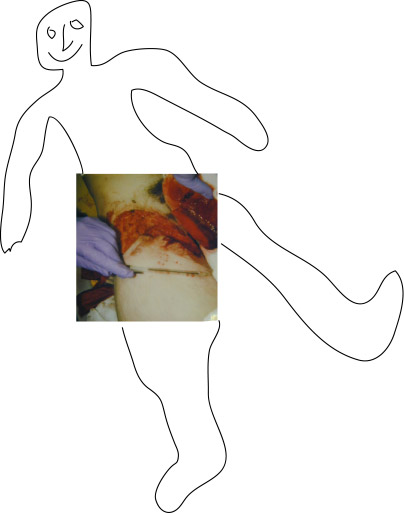

Click on the image above to see a larger view of a photo taken at the emergency room. The person sketch above ought to help you orient the picture. Warning: it's not pretty. |

It was a warm, clear afternoon. I had left for a ride around 4:30 PM, planning to either go around Mercer Island or over the north end of Lake Washington. Passing through the U-District, I met up with another rider named Walt Nestelle, a racer from Anchorage who was visiting for a while. He'd never ridden Juanita Creek Drive, so we joined up to do the north end of the lake. We had good riding across I-90 and up through Bellevue and Kirkland, pushing it a little harder than a normal training ride. We took it back a notch up the hill on J-Creek (hr's in the 150--160 bpm range). After passing QFC at the top of the hill we started down toward the Burke-Gilman.

As we approached the first traffic light on the descent, there was considerable traffic in our direction moving slowly. We were going about 20 to 25 mph on the right side of these cars, riding in the generously wide shoulder and overtaking the traffic. Riding in front of Walt, I had my fingers on the brakes, hands on the brake hoods. I recall looking ahead and seeing the light at the intersection about 100 meters in front of us. It was green and the traffic seemed to be moving forward. I perhaps looked back to shout something to Walt. I do recall exclaiming platitudes about the fine weather, the golden sunlight through the trees, etc.

Next I knew, a green sedan was turning left in front of us. A motorist on our left (going in the same direction as we were) had stopped to allow the sedan to turn from the oncoming lane. The driver in the sedan did not see me nor Walt until he was well into the shoulder we were riding on. Talking to him later, he said that when he did see us, he accelerated and tried to get out of our way. Walt had apparently seen the top of the green sedan over the roof of another car, and was able to brake and avoid hitting the car. I yelled "Car!" to Walt when I saw the car, turned to the left, slightly, and hit the brakes. I rembered thinking, "Should have been more sensitive on those brakes" as I felt my brakes lock up and my tires skid. I don't think it would have made much difference anyway. There was very little time before I hit the car.

Walt, watching from behind, says my bike crabbed slightly, and then I rode a small nose wheelie into the car. I remember looking down at my front wheel, wondering if I had a chance of bunny-hopping it and the bike over the trunk (of course not!). I tried to jump at the last minute before impact. I don't think I got very high. Walt says it looked like I did jump off the right side of my bike. I heard a thump, and then very quickly rolled off the car. I must have slowed considerably in hitting the car, because I landed almost directly behind the two rear wheels.

I ended up lying on my back/right side. I could see Walt getting off his bike telling the driver, Mark, who had a cell phone, to dial 911. Then he told me, "I'm trained in emergency medicine, don't move. Just stay where you are." This was my first accident/injury in which I had felt there was considerable potential for spinal damage, and so I was quite content to remain motionless. The driver asked me, "Are you all right?" to which Walt screamed back, "Of course he's not all right! You just ran into him! You dial 911!" The two did not get on famously for the remainder of the incident.

Ten years earlier I had received Emergency Medical Technician training at the Wilderness Medicine Institute in Pitkin, Colorado. I felt strangely calm, and much of what I learned came back to me. My right thigh hurt tremendously, and I was worried I had fractured my femur: "Walt, I want you to hold my right leg a little above the knee and pull five to ten pounds of traction on my leg." Walt did this, pulling a little hard at first, but then finding the right balance and stabilizing my leg. (When the femur fractures, a common response is spasm of the quadriceps muscle, which sometimes causes the fractured ends of the femur to burst out of the skin of the leg, becoming a "compound" femur fracture. Pulling light traction on the leg reduces the chance of this.)

The primary concern with femur fracture is severing the femoral artery---a very serious medical emergency. I asked Walt if he could see any blood spurting or pooling around me. None, fortunately! By this time, Mark had gotten through to 911, and I told him to tell them I was a 30 year-old male with a possible femur fracture. Then I went back to seeing what else was wrong. By now, 35 seconds or so had passed and I wasn't showing any signs of shock, at least as far as I could tell. So this was a good sign that I might not be bleeding badly. Someone else had shown up on the scene and asked me if he could lift up the top of my cycling shorts to see how things looked. At this point, by looking down, I could just see my right leg. Underneath my shorts it appeared as though someone had poured half a can of Spaghetti-O's onto my inner right thigh. However, I couldn't see any fractured bone ends and no arterial gushers or spurters. I figured that I probably had a small avulsion on my inner right leg. He put my shorts back and I let my eyes roll back and tried to relax.

Someone put a jacket on me to keep me warm, but I asked them to take it off so that people could continue to inspect me if necessary. There must have been a lot of activity. I remember a few things distinctly. I asked for someone to get a piece of paper and a pen and to write down that I was 30 year-old grad student at the University who was Awake and Oriented times 4. Then found my carotid pulse and asked someone with a second hand to give me 15 seconds. 17 beats = heart rate of 68 beats per minute. ("Write that down!"). This was great news! If one is going into shock (basically dramatically reduced blood pressure) after injury, the heart usually tries to compensate by beating faster. The relatively low heart rate suggested that I wasn't losing too much blood. I then gave my father's name and phone number in Alaska, and told people there that I was covered by the Graduate Appointee Health Insurance at the University.

A guy named David showed up and put an ice pack on my leg. I asked if there was anyone around who knew how to take a pulse off my wrist so I could get another reading. David said he was an R.N. and had already done that. It was 64. Still no sign of shock. Soon after this, a uniformed police officer with B. C. Turi embroidered in yellow on his shirt came into my field of view and told me the paramedics were right behind. Though my sense of time was probably a little skewed, I don't think that it had taken the paramedics longer than 3.5 or 4 minutes to arrive. I was unspeakably glad to live in a city with a model Emergency Medical Services system.

A moment later, a very reassuring-looking guy named Michael Morse showed up with a crew from the fire department. He asked me how I was doing and what had happened while someone else stabilized my head and removed my helmet. These guys knew exactly what they were doing. The first thing they did was remove my right shoe and check for a pedal pulse, which they were able to find---further good evidence that my femoral artery was intact. Michael asked if I had been unconscious at all. I said no, and a dark-haired woman at the scene concurred that I had been fully conscious at all times. They gave me a nasal cannula with low-flow O2. Someone pulled out a pair of blunt end scissors and went to my right leg. Having now seen the picture taken at the emergency room, the view of the wound thus offered by snipping off my shorts must have been somewhat disturbing, at least to the onlookers. However, I didn't catch on at the time, and still believed that I must have had a small avulsion with a possible, well-contained femur fracture. I overhead one of the paramedics say that "It looks a little high for a femur fracture." Someone (probably Michael) did a full physical inspection for other injuries, checking particularly for abdominal pain, evidence of abdominal bleeding, and signs of pelvic fracture. Three weeks later I got a chance to talk to Michael one evening at the Lake Forest Fire Station. He said that my bike shorts had only two very small holes in them on my right leg, so that it seems the soft tissue damage was not due to impaling or cutting myself on something large and sharp but rather by avulsing the skin through the shorts. He also mentioned that he thought much of the injury may have occurred from catching my leg on a small spoiler on the back of the trunk as I flew over the back end.

They got the spine board out and prepared to roll me onto it. The guy at my head was coordinating the effort. As the crew was getting set up around me, the green sedan apparently rolled backward toward them a few inches. I think the driver had gotten back in it to move the car. There was a lot of hollering as they made sure the emergency brake was put on in the vehicle. Then they rolled and slid me into position on the board. I caught someone's attention and told him, "I'd like to ask just one thing. Please pad the back of my head when you board me." He said he would see what he could do about that. At WMI, the instructors had stressed the importance of patient comfort in extended, wilderness-emergency care, and padding heads was a big issue. Furthermore, a friend of mine had broken his femur in a climbing accident at Joshua Tree Natl Monument about twelve years earlier. The ambulance crew had boarded him at the scene without padding his head and drove him several hours to a hospital. By the time he arrived, he said he couldn't feel the pain in his leg over the intense pain in the back of his head, and he developed severe bruising on the back of his head as well.

After I was lashed down and my head was blocked and taped to the board, I asked if I could be taken to UW Medical Center because my health insurance compensates at a higher rate there. Michael said that, although they often give patients a choice on which emergency room to go to, the traffic was too bad and my situation too serious to consider getting to UW. They were going to take me to Evergreen Hospital instead. I told Michael I was scheduled to meet a friend for dinner at a restaurant in Green Lake. He took down the info, and told me he would make sure that someone called the restaurant and relayed the message that I had been in an accident and was off to the hospital.

The police officers seemed to be heading back to their car. I asked them how the driver was doing.They said that everything had been taken care of, and that Officer Turi's business card would be sent with me to the hospital. One of the guys from the fire crew had gotten my bike and said that it looked to be in remarkably good condition. He said they would hold it for me at the station until I had a chance to pick it up. As I was getting lifted into the ambulance, Walt said that he had left his number with me---that I should have it at the hospital---and "Call me!"

I thanked Walt for his support at the scene of the accident, and also for what had been, up until the accident, a simply dreamy ride. He told me it was one of the most enjoyable rides he had done while in Seattle (this improved my spirits considerably!) and that he looked forward to me coming up to Anchorage for some skiing when I was recovered. Then I was in the ambulance and they were getting ready to drive me off.

I was accompanied in the back by Joe. He said I didn't need to talk much anymore and gave me an O2 mask over the nasal cannula, telling me that it looked like I was doing OK---that I was "in front of the curve" at this point, but that they were going to take every precaution to make sure I stayed there and didn't slip "behind the curve." He said he had some stuff to do to get me ready for the ER, and asked, "Are you very attached to your shirt?" As it happens, it was one of my favorite cycling jerseys, but I don't think that would have made much difference anyway, as he was getting set to cut it off me with a pair of scissors.

I asked him how things looked on my leg. But he didn't want to offer too much information. He just said that I had managed to do a fair bit of damage and had a laceration on it. When we arrived at the hospital, they pulled me out and wheeled me in. I was struck by this new perspective---I had never before had such a vantage point from which to contemplate the ceilings of a hospital with all the different patterns and types of lighting fixtures. My vision blurred a bit when they took me out of the ambulance, and I reported this to the medics, but figured it was just the result of going into a darker area after being in the well-lit ambulance.

When I got into the emergency room, one of the first things they did was get an IV line into my right arm. The nurse wasn't able to stick my forearm (rather strange, because I have some sizable veins there). In the end she went for the vein on the inside of my elbow. Some more people arrived including a charming woman, Dr. West, who was the doc on call that night. I overhead somebody say something about a "twelve-inch" laceration on my leg. That settled in for a few moments before I was able to reach out and grab the nearest arm on my right and ask, "Excuse me. Did someone just say twelve-inch laceration?" They assured me that it was a doozie. A bit later, a searing pain came from my leg. I thougtht perhaps that they were sticking a needle into it to inject some local anaesthetic. But they were just pulling out the gauze that the paramedics had packed into the wound. Somewhere along the way, somebody came in for me to sign some papers. They make an effort to get informed consent to treat early on, before they administer any pain-killers. Shortly thereafter they started dripping Dilaudid in via the IV. They called in an X-ray tech with a mobile unit to snap a shot of my femur. He told me that he had broken his femur some years back and had to be in a cast for six months. This left me praying for intact bones. After he left, most everyone else seemed to also leave, and suddenly I was left feeling somewhat alone. After a couple of minutes I was feeling very alone and started asking, in an undoubtedly mousey little voice, "Uhhh....is anyone there?" It turned out that Joe from the ambulance was sitting quietly next to me (my head was still boarded so I couldn't see him) possibly filling out paper work. It was good to know he was there.

Shortly, Dr. West came back in and raised her arms in a victory salute (she actually extended her arms horizontally over my stretcher so I could see them, but the effect was still uplifting). My femur was all right! Then people went back out, leaving me to cry tears of relief quietly to myself. Some nurses came in later to take stock of what possessions I had. They catalogued the bike shoes, helmet, heart rate monitor, etc. that had arrived with me, and put it in a bag which I would get the next day. Then I had to wait until the X-ray room was free so they could get shots of my spine and neck, and a few more of the leg. By the time I got in there I had been taped to the board for a good two hours, probably. At this point, the nauseating pain from my occipit suggested that the medics had not (!) padded the back of my head. I the X-ray tech verified that there was no pad there. By the time the last X-ray was being taken, the pain in my head easily rivalled the pain in my leg. Fortunately, by that point my arms were free and I could work my fingers under my head to relieve a little bit of that pressure.

The X-ray tech was a personable guy. He had a brother in med school and was taking classes himself to become an MRI technician. We talked a bit about my statistical genetics work at the UW. I commended him on his use of the lead blanket for covering my privates. He replied, "Well of course! I'm protecting your genetics. You know all about that." We had a good laugh at this.

Once the films came back, I got the go-ahead to take the neck collar off and be a little more mobile. I got to call my friend Alan Haynie. It was great to hear his voice. He took messages from me to relay to a few other folks, including my dad. Later on I tried giving my dad a call. The line was busy several times. One of the nurses asked if he might be logged on with a modem. I offered that he was probably surfing porn---every bit of humor, even of poor taste, seemed to help.We tried to get the operator to do an emergency breakthrough but she was unable to. As it turned out, one of the main fiber optic cables connecting Alaska to the rest of the world had gone down that evening, and all the circuits were busy. The Kenmore police officer had actually gotten through to my dad's answering machine earlier in the evening and reported that I had gone to the hospital with a compound femur fracture. By the time Dad got the message, the circuits were down. He ended up leaving a day early for a trip to California and catching a flight out that night, reaching Evergreen Hospital the following morning---what a guy!!

While waiting, I overheard the patient in the next bed. Not a happy scene. There was a distraught mother there with her son who was still unconscious from over-drinking alcohol. Fortunately, it seemed he would be all right, but it was still going to be a while before he woke up.

Later on I got to meet the surgeon, Dr. James Mhyre, who was on call that night. My injuries were deemed serious enough to require surgical repair under general anaesthsia. He then went off to scrub up while they prepared the operating room. Then some nurses showed up with a Polaroid camera. I had requested earlier in the evening that I get a picture of the injury before they closed the wound. Now that it's all over with, I'm glad I got the picture, I hadn't really gotten a good chance to see the thing. One of the nurses set the leg up to photograph it. In the photo, one hand (and I must say the vibrant purple gloves made my day!) is holding a pen, while the other is holding what appears to be a bloody piece of flesh, but which is, in fact, merely a gob of blood-stained gauze. What isn't shown was his first attempt at taking the photograph. After assuring me that I would really want something in the photo for size reference he dropped his jaw as the pen he had rested on my leg rolled down into the wound. This was not what I wanted to see happen, though he assured me that everything would get well hosed down and cleaned up in the operating room.

After a little more waiting, they sent me to the OR.

After they wheeled me up to surgery, I got to meet the anaesthesiologist. She said that the neck X-rays had not been conclusive and that they thought it best that I continue to wear a neck collar. A nurse fumbled an ill-fitting collar onto me. Then she told me that when the time came she would administer some IV medication that would make me feel drowsy, and then let me breathe through a mask with some stuff that would put me under. After that they were going to quickly intubate me (stick a tube down my trachea to maintain a good airway) and they'd keep me breathing fumes until the surgery was over, then they would shut off the gas and I would wake up in another ten minutes or so. After that cheery description she went away for a while and I tried to call my father again.

Dr. Mhyre and the anaesthesiologist returned and doped me up. I remember being given a mask to breathe in. I was told it would smell a little plasticky. It seemed vaguely sweet. The next thing I remember, I was coming to and someone handed me a phone. It was about 2 AM and my father was on the line. He was able to call from the airplane. I told him through wildly slurred speech that my femur was all right and a bunch of other things that he probably already knew anyway. He told me he would be at the hospital after six in the morning.

I was moved to a hospital room. The nurse had a British accent. She was very proper. Unlike the other nurses, she wore a tightly-pressed white suit with a big blue sash/belt around her waist. She also had what appeared to be a medal pinned to her breast, along with a small pewter sailing ship, or an anchor, or some other object of nautical interest. I can't recall exactly what, but I do know it lent a slightly surreal air to the whole situation. The tech on duty urged me to drink lots of cranberry juice to assist in the post-operative milestone of my first urination. I kept the poor guy coming back at regular intervals to fill up my glass.

Finally the time came to acquaint myself with the plastic, hand-held urinal. What a magnificent piece of ergonomic engineering. Being no stranger to productive kidneys, I dare say that I have experimented with a wide variety of bottles, tins, and any other handy vessel to assist in my relief during long road trips and cold nights in snow caves, etc. Never before did I know what miserable implements all of them were compared to the Vollrath A-21 Disposable URINAL of recyclable high-density polyethylene. Despite the profusions of praise I have for this little plastic marvel, it was still only with considerable effort that I was able to let 'er rip while lying down in bed. Thus pleased that I had cleared the first hurdle of my post-op recovery with only minimal wetting of myself, I drifted off to sleep for a few hours.

I awoke for the last time that morning at 5:30. It was at this hour that my room mate decided to start channel surfing. Our television received many channels I had never heard of before. At this early hour, most of them were broadcasting shows I had not seen since my years before junior high. After a dizzying spin through the offerings, my roomie (Ian, he was called, I think) settled on Ponch and John riding their gleaming motorbikes along Los Angeles' sprawling freeway system. At the time I could not remember how the theme song to CHiP's went, and even after that morning's little refresher, I would be hard-pressed to hum three bars of it, but it was strangely comforting to hear it, nonetheless. When that ended we proceeded to consume a Simon and Simon re-run. Then we had back-to-back episodes of ER. It was very strange to be watching that from a hospital bed.

Ian had already spent four days in the hospital recovering from an incarcerated hernia. In this unfortunate phenomenon, a piece of large intestine had gotten tangled up through a small rupture in his abdominal wall and had been strangulated. Doctors had performed an emergency resection of two inches of his colon. I was ironically very interested in this because I had been recently diagnosed with an inguinal hernia and was scheduled for a consultation the next week with a surgeon at UW to talk about fixing the hole. Ian, not surprinsingly, strenuously recommended that I get it taken care of as soon as possible.

Somewhere in the midst of our 1980's TV-fest, Dr. Mhyre came in to check on me. He told me how the surgery went. The extraordinary news he had to report was that things were actually much worse off in my leg than it appeared from the outside. When he started poking and prodding under the distal flap of skin he discovered that much of it and the underlying fascia had been stripped away from the muscle, severing lots of nerves and blood vessels. He said that he was able to put his hand under the flap like it was a good-sized pocket in a pair of pants. Pictorially, if you go back to the Polaroid it means that much of the skin visible toward my knee on the inside of my leg is a big flapper (or a "goby" as climbers might call it...a real big goby!) The good news was that the muscle was still intact in its sheath. He seemed to think that I had impaled myself on something because he said he had to clean some hair and junk out from deep within my leg and some fat seemed to have been scraped off my quadriceps muscle. A rather crude form of liposuction, I suppose.

Dr. Mhyre had put a Jackson-Pratt drain under the flap of skin. So, he sewed my leg up at the top end, but cut a small hole in my leg near the bottom of the flap and ran a little piece of flexible hose out of that. The hose is perforated to wick blood and stuff out from the wound and into a little bulb on the outside of the body. By morning I had dripped only about 35 cc into the bulb---not too much.

Shortly my father arrived. It was great to see him. He's a physician, so he was able to fill me in on a lot of the details of what seemed to be going on. I got a few calls from friends who had heard about my accident. It was great to hear from them.

The rest of the day proceeded slowly. I had to wear the neck collar until the late morning while we waited for the CT scan to become available. What a great machine. You get inserted into a big tunnel and it takes panoramic images of your insides. They wanted to make one final check on my neck. My dad went down to read the images with the radiologist. My neck showed no signs of injury, and according to Dad, no signs of aging degradation in the discs. It's always good to know I should get a few more years out of this ol' bod.

The best part was when one of the nurses came to yank the drain out of my leg. She gave me Demarol (a powerful narcotic pain-killer) via IV. I didn't like that very much. I became secretly convinced that she had put too much in and that I would slowly dip into coma and eventual death. Her next action, though, helped me to be quite certain that I was still more conscious than I wanted to be---slowly and with great deliberation she drew what looked like a flattened computer cable out of my leg. Twelve inches of it, in fact. To be honest, it was an exquisite sensation. Not unlike getting large sutures removed, but ten times more bizarre to feel something that large snaking around under your skin.

I was discharged at about 3 PM on Friday the 6th of October. My father drove me home by way of the Kenmore Fire Station to get my bike. Miraculously it had suffered what appeared to be no more than about 25 dollars worth of damage. The grip tape was a little scuffed and the right shifter/brake lever assembly hood was cut and pushed around a bit. The front wheel was hardly out of true---it wasn't even rubbing on the brake. Totally unbelievable.

When we reached my home it was clear that I would not be able to get up to my room without extra help. Dad went for some takeout food. When he returned I sat in the front seat of the car, while he sat on a chair that he had gotten from inside. We shared a really nice evening. It was clear and warm and several crocuses (crocii?) were blooming in the planter next to the street. Eventually my housemates Josh and Eli showed up and with my dad's help they were able to carry me up the stairs to my room.

I refer the interested reader to a concise and picturesque

account of my recovery authored by the Scansorial Scot, that

master of digital-image debauchery, Scott Veirs. This account

resides on his very own server at:

http://www.econscience.org/eric/lac/recovery.html